West End - Louisville, KY USA [2025]

In 1915, Charles Buchanan, a white homeowner, agreed to sell his property in a predominantly white Louisville neighborhood to William Warley, a Black attorney and representative of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The sale was contingent upon Warley's legal right to occupy the property. However, a Louisville ordinance prohibited Black individuals from residing in majority-white neighborhoods. When Warley refused to complete the purchase due to this ordinance, Buchanan sued, arguing that the ordinance infringed upon his property rights and violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) - Justice William R. Day delivered the unanimous opinion of the Court, emphasizing that the ordinance unconstitutionally interfered with the freedom of contract and property ownership. While the unanimous ruling struck down racially based zoning laws imposed by municipalities, it did not prohibit racially restrictive covenants, which were later used to maintain segregation in housing.

Racially restrictive covenants were contractual agreements embedded in property deeds that prohibited homeowners from selling, leasing, or transferring property to individuals of certain races, particularly African Americans, Asian Americans, Jewish Americans, and other marginalized groups. These covenants were widely used in the early-to-mid 20th century to enforce residential segregation, even after the Supreme Court's ruling in Buchanan v. Warley (1917) made explicit racial zoning laws unconstitutional.

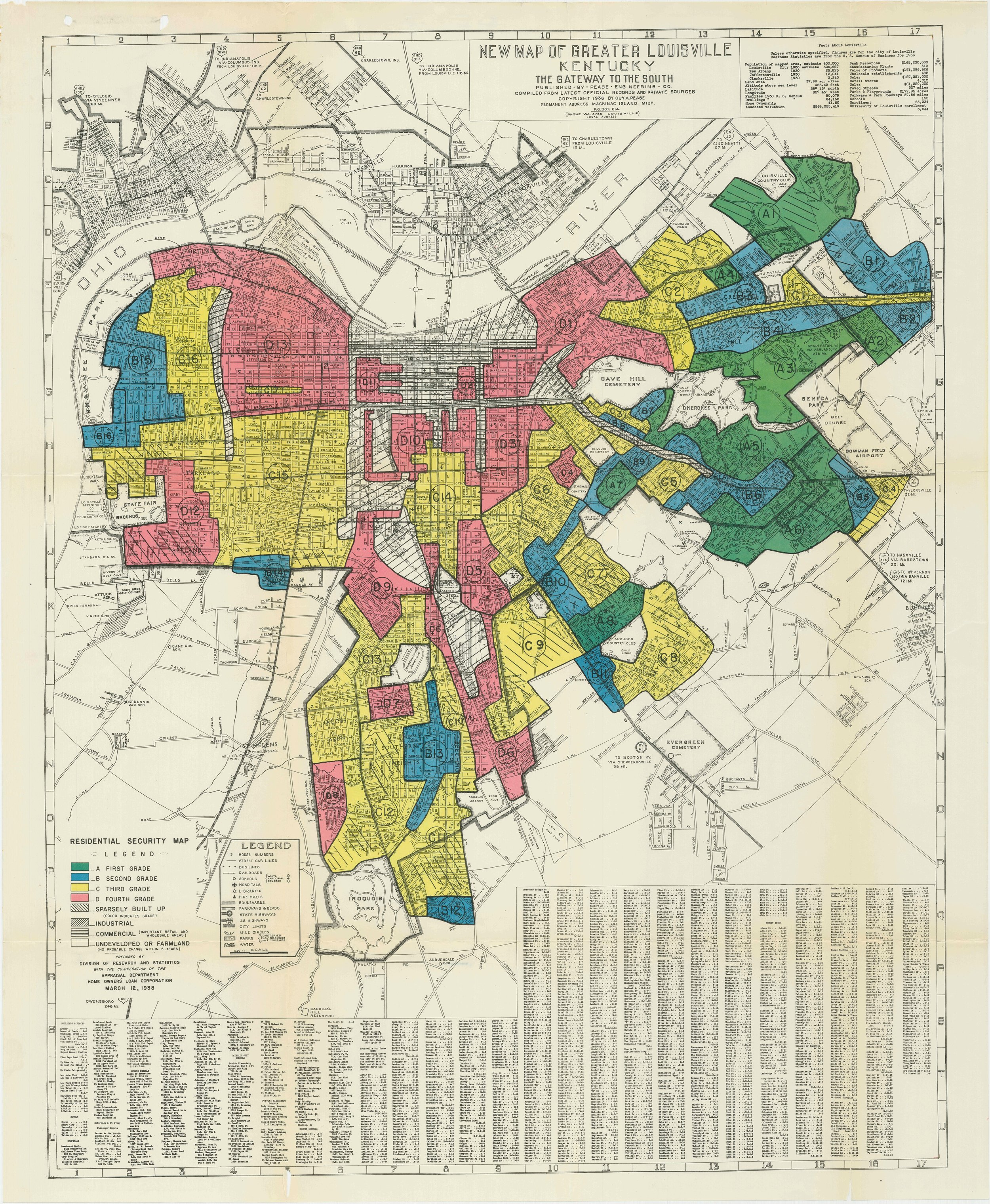

Louisville, Kentucky's urban development throughout the 20th century was significantly influenced by policies and infrastructure projects that shaped its demographic and economic landscape. Key among these were redlining practices and the construction of major highways like Interstate 64 (I-64), particularly the 9th Street exit. In the 1930s, the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) implemented redlining, a discriminatory practice that graded neighborhoods based on perceived investment risks, often linked to racial composition. Predominantly Black neighborhoods were frequently deemed high-risk and outlined in red on maps, leading to disinvestment and limited access to mortgages for residents. This practice entrenched racial segregation and economic disparities in Louisville.

SOURCES

"Redlining Community Dialogue." LouisvilleKY.gov, https://louisvilleky.gov/government/redevelopment-strategies/redlining-community-dialogue.

"Dividing Lines: Redlining in Louisville." Louisville.com, https://www.louisville.com/redlining-louisville-dividing-lines.

"Redlining Louisville." LOJIC, https://www.lojic.org/redlining-louisville-news.

"Redlining Louisville Project: Early Lessons Learned." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/bridges/summer-2017/redlining-louisville-project-lessons-learned.

"Louisville's History of Racial Oppression and Activism: Housing." University of Louisville Libraries, https://library.louisville.edu/archives/racial-logics/housing.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917). Justia, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/245/60/.

"Buchanan v. Warley." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/245us60.

"Buchanan v. Warley." Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/245/60.

"1917: Buchanan v. Warley." Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1917-Buchanan-v.Warley.html.

Residential securities map

Although redlining was officially abolished in 1951, its repercussions persisted. Subsequent urban renewal initiatives were spearheaded by Harland Bartholomew (1889–1989). In the late 1920s, Bartholomew was commissioned to create Louisville's first comprehensive plan. His work led to the publication of "A Major Street Plan for Louisville, Kentucky" in 1929, which outlined strategies for the city's infrastructure and segregation. In the 1950s and 1960s, his urban development plans led to the demolition of significant Black business districts, notably along Walnut Street (now Muhammad Ali Boulevard). This displacement further marginalized Black communities and eroded cultural hubs.

“The Federal Housing Administration's (FHA) Underwriting Manual” provided guidelines for property appraisal and mortgage insurance underwriting during the mid-20th century. Excerpts that appear in the 1936 edition of the manual, within the section discussing "Protection from Adverse Influences,” suggests that natural and artificial barriers, such as high-speed traffic arteries or wide street parkways, can serve to separate and protect desirable residential areas from what it termed "inharmonious uses" or "adverse influences." This language reflects the FHA's policies which promoted segregation and contributed to systemic racial discrimination in housing.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 spurred the construction of interstate highways across the nation, including Louisville. I-64 was developed during this period, with its path cutting through urban neighborhoods. The 9th Street exit, in particular, became a physical and symbolic divider between the predominantly Black West End and the predominantly white central business district. This division reinforced existing racial segregation and contributed to economic disparities between these areas.

TIMELINE OF KEY EVENTS

1917: Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60

1920s: Harland Bartholomew is invited to Louisville to create the city’s first comprehensive plan.

1930s: Implementation of redlining practices by the HOLC, leading to systemic disinvestment in Black neighborhoods.

1951: Official end of redlining; however, its effects continue to influence housing and economic patterns.

1956: Federal-Aid Highway Act accelerates interstate construction, including I-64 in Louisville.

Late 1950s - 1960s: Harlan Bartholomew and Associate return to Louisville with an updated city plan. Urban renewal projects result in the demolition of significant Black business districts, notably along Walnut Street.

1960s: Completion of I-64 and the 9th Street exit, exacerbating the physical and economic divide between Louisville's West End and downtown.